At uncertain times, a man of faith must lean heavily on a man of the cloth. Amid the brutality of irregular warfare, Cardenas found no writs in his holy book on how to deal honorably with a cruel adversary. The Viet Cong, for instance.

It was mid-1967 in Central Vietnam. Debates about strategy were becoming more difficult among field commanders. Tacticians insisted on Cardenas joining them in their strategy. They favored the ruthless search-and-destroy methodology of regular warfare. The captain felt grossly misunderstood by insisting on counterrevolution more than the hunt-and-kill concept. He had seen enough bloodletting at the Iron Triangle.

Ulises saw the officer suffer quiet, unexpurgated pangs of disgrace when marked for a possible dereliction of duty. A pang that stung his pride more than his conscience. The captain felt the need to consult with his spiritual guide. He summoned his old friend, Major Enzo Santangelo, to Rumba Hill for a soul talk.

Duquel was tasked with locating the usually busy man of the cloth and bringing him to Cardenas. The captain’s bunker posts was to be an informal confessional.

Once a street punk from Boston’s North End, at 51, the Catholic priest was serving his third tour in Vietnam. He joined the US Army in 1944 as a graduate seminarist with the Paulist Order. Trained at Fort Benjamin Harrison for his chaplaincy. It was a time of strong spiritual vocations. Military chaplain schools were full in the United States. The heathenized fascism of Nazi Germany shocked many youth of the time. It was also in response to the atheistic secularism of Communist Russia. After his graduation at Fort Devens, Massachusetts, Santangelo served with field troops in the Pacific campaign. Then, through the Korean conflict. He eventually became Brigade Chaplain for the 25th Infantry at Schofield Barracks in Hawaii. There, at the Oahu base, he befriended a First Lieutenant Ruddy Cardenas.

At Da Nang Evacuation Hospital, the cavalier chaplain kept busy at the triage wards, spiritually comforting the gravely wounded. He frequented the Medical Aid Stations. His mission was to minister the last rites of the church to the dying soldiers, praying for an exit with absolution. He wrote consolation letters to the kin of those killed in action. No one envied his job. At other times, Santangelo dealt with troublesome soldiers. This included a few of Cardenas’s troopers. He appeased the fierce Buck Sergeant Guillermo Espino a few times. Also lent an ear to the mortified Combat Medic Josiah Rawlings.

When Cardenas sent Ulises to fetch the chaplain, Santangelo was busy at the field hospital wards. Instead, he scheduled a visit for the upcoming Sunday. He often served mass atop Rumba Hill because as Latinos, most of Cardena’s Tango troopers were raised in the Roman Catholic faith. The warrior priest officiated at a rustic open-air chapel that Radioman Thibodeaux built from discarded ammunition boxwood. He half-walled it with sandbags in case of a mortar attack during prayer time. A beat-up aluminum mat from the Chu Lai airfield became the altar. Patiently, Thibo polished it to a mirror finish with Brasso. A pious country boy from deep in the Missouri woods, he prayed the rosary each night during guard duty at the firebase perimeter. On one hand he held the beads, with the other fingering the M-16 safety latch. His eyes fixed on the Claymores planted in the empty fields beyond the perimeter wire. Only at war would a man pray for redemption while ready to eradicate a part of humanity.

On festive Sundays, Cardenas—a modest practicing Catholic—regularly confessed and took communion. Santangelo trained Ulises as an impromptu altar boy. On the designated Sunday, he observed the captain kneel during the short, private confessions inside the bunker from afar. He always wondered in what manner avowed battlefield commanders, such as Cardenas, confessed their sins.

Forgive me, Father, for I have sinned. This week, I knowingly sent five of my soldiers in harm’s way, had ten enemy fighters killed, mutilated another few, firebombed a civilian village, and displaced twenty innocent families from the ancestral homestead after my troop trampled all over their cultivation fields, handing the confiscated property to corrupt local officials.

Duquel found the days at Hill 54 were surprisingly quiet by the end of May ’67. It was a tense calm. The old hands knew that something bad could be in the offing whenever the local guerrillas were still. May was the ripe rice season in Central Vietnam. The peasants toiled heavily in the foothills and terraces, cleared ditches, and shored up the dikes for the harvest. Rice stalks grew tall and yellowish, stamping the landscape with a gilded glow in the afternoons and the early dusk. Spring also marked the onset of the rainy season.

Surely, assumed Ulises, the insurgents were busy reinforcing tunnels and lairs. They filled bomb craters along the snaking infiltration routes crisscrossing the Annamite Sierra under the heavy jungle canopy. Everyone felt humid and sweaty. The troopers bathed in small groups of two or three in the nearby hilly streams to avert an ambush.

After mass that Sunday, Cardenas retreated to his bunker with the Chaplain for personal consultation. He ordered Duquel to stand guard outside to prevent interruptions.

“Your conversation will be private, Sir. I should not be around,” Duquel advised.

“Stay put. I need to document it all down for when I am called to answer for my actions. That is why I have you near me. Also, make sure no one else hears what we say here today.”

When Santangelo arrived, the officers went immediately to matters at hand.

“I want to open my soul to God through you, Enzo,” said Cardenas with a muffled voice.

“What ails your heart, dear brother at arms,” the Chaplain replied as if in a confessional mode. Two pious warriors in discreet dialogue. Ulises mused about Medieval monks confessing before going on crusades to annihilate heretics.

“I’m all tensed up with this matter, Father. I don’t want to be nonmilitary, but I feel mistreated by my superiors.”

Santangelo shifted to a more colloquial tone. “You know I’m a Combat Chaplain, Ruddy. I’ve officiated mass inside bomb craters. Gone from foxhole to foxhole with prayer. My prayer book and I are always on the move. It is fitting that I pray for the dead in the actual spot where they lost their lives. Is it that you’re having a battle death intuition?”

“Of course not. I lost the fear of dying in combat a long time ago.”

“Death is constant in our milieu. My service in the aid station at Da Nang is a crisis ministry every hour of the day. I am aware of the unspoken agony and the hunger for spiritual tranquility. So, speak to me, Ruddy.”

The captain rubbed his chin hard. “I am in resentment of my superiors, Padre. I need to know if, in the eyes of God, such sentiments are a defect of character. Is there a lack of military discipline? Am I in tune with moral rationality?”

“Let it be known that your bosses have privately expressed concerns about your attitude towards the established order of battle. Not as criticism, but taken aback by you,” the chaplain countered. He brushed his short-cropped, silvery hair nervously with both hands. His small, grey eyes flashed curiously. “Your bitterness may have valid reasons.”

“I wish you could read the absurd orders that Battalion Headquarters cut out for my new mission in Central Vietnam. They are demeaning,” said Cardenas in a tone of complaint the chaplain knew was unusual. “Even allowing a green officer to redact my field duties is tantamount to relief of command.”

“During my long military ministry. I’ve learned that field commanders are ferocious territorial animals. They don’t like things happening out of their purview. You’ve pissed off a few of the brass at Brigade Headquarters.”

“I distrust field commanders who want to be clueless about Vietnamese culture. Some say Vietnam’s history is of no strategic value for present field operations.”

“You surprise me, Ruddy. I always regarded you as a tough field officer with a hard line against Communist aggression. You’re becoming contemplative.”

“I’ve been tempered by the carnage of this war. Have deeply studied Vietnamese tradition and discovered its relevance. The American military must understand what it builds or destroys. This understanding is crucial if we are to be an arbitrator of change in this land. We may irrevocably alter the ancestral order of things just to keep a few people in power.”

“Reasonable enough,” said Santangelo. “But commanders don’t’ see that as a mission. How will all your scholarly incursions help the chiefs to strategize? Explain it to me, and perhaps I can have them better understand your intent.”

“The brass in Da Nang knows damn well what I am proposing, Padre. I’ve discovered many layers in this insurrection and told them we need to rationalize it. Our adversary has awakened its ancestral domination psyche. We need to gauge if our South Vietnamese allies have the military and political will to resist being overrun.”

“Those are big concerns, Ruddy. Military mess-ups always degrade the losers. The United States will lose face if this involvement is not properly steered.”

Cardenas stood up and paced about the bunker with a pouncing attitude. Sometimes, he took on the carriage of a Yaqui warrior.

“We could easily be heading for a big fuck up,” he said. “The French already went through the grind here in Nam. And many other conquerors at other times and other places. Including my paladin, Hernando Cortés, Belgians in Africa, Brits in India, Italians in Ethiopia, and others. Conquerors are blind to the consequences of their conquests. Their minds are on the prize. On the spoils for exploitation”.

“Sadly so, Ruddy. Political malpractice. I won’t go into a dark litany. However, my church has been historically complicit in oppressive occupations. Despite the good spiritual intentions, Rome has connived with the wrong Ceasers. With secular power grabs. I am consoled by the belief that the Almighty does not place evil designs into men’s minds. Greed does, and no institution is free of greedy arbitrators.”

“Some things are not worth defeating,” Cardenas said pensively. “Except anything that smacks of Communist rule, which is to say a godless society.”

“Uh, it was some 75 years ago, I think. The Catholic church officially condemned Communism. But it’s a never-ending struggle. Here we are at it again in Southeast Asia.” Santangelo had a tall, skinny bearing as if stricken by famine. He suffered from chronic indigestion. Intolerant to cold C-rations and unfiltered water. As a result, he went without rations for days during long field operations.

g long field operations.

Cardenas shifted tone again. He now took on a more affirmative voice. “As the higher-ups define our military objectives in Vietnam, I adhere blindly to the mission. However, middle-echelon commanders must allow field officers with different competencies. They should decide how to execute it in their nook of the battlefield. Field officers must have the option to identify what to destroy and what to leave alone.”

“You’d have to be at least a brigadier general for that,” joked Santangelo. “Colonel Gallagher insists we came to Vietnam to fight a bone and flesh enemy. The invisible ones are not on our tactical maps. It’s a messy fight. The Viet Cong has an encyclopedia of atrocities. It worries me spiritually that we are fast learning from them.”

“The old ear for an ear doctrine,” retorted Cardenas. “I stopped cutting Viet Cong ears a long time ago. We have only been here in full force for two years. A new pattern of savagery emerges with each skirmish. I say we fight a more elegant war, one of destabilization, not one of slaying.”

“I spiritually agree with that, Captain. But how do you explain it to an infantryman who lost three friends in an ambush? How do you tell a field commander who had half his troops wiped out in a single battle? I’ve seen many hearts fill with revenge,” said Santangelo.

“We can turn this revolution over by tuning deeper into the North and South Vietnamese patriotic psyche. Common nationalist sentiments and historical events bind them strongly in traditions and values. If a centrist power structure is set up, and unification achieved, this civil war is over.”

“You see the American role as a mediator more than as a military enforcer?”

““I see we have inserted ourselves into a ferocious street rumble inside an Asian, broken neighborhood. France fractured it long ago and then abandoned it. I see no military solution for this except more rivers of bloodshed. Diplomacy, political ingenuity, and well-funneled economic aid are the only hopes.

“The truth is that both sides are fighting for similar historic ideals. Yet, they are so politically apart. Contrasting ideological reasoning and old grievances blind each side from convergence.”

“It is up to us to develop for the Vietnamese a functional system of governance that serves common national aspirations. First, there must be disarmament. Unification is also of the first order. Next, a shared power structure. Follow up with economic development of mutual interest. All under international military supervision.”

The chaplain frowned comically. “You’ve become a mischievous spirit, Ruddy. The wizard of Southeastern Asia diplomacy. Diehard Hanoi revolutionaries, nor South Vietnamese power elites will allow it. Their visions of what democracy is are too abysmal.”

“Democracy is for the eye of a beholder. In this case, it is about finding common Western and Oriental values that best fit a new Vietnamese psyche. Discard the rest of the traditional ideas,” insisted Cardenas.

“I see you are proposing a new mindset for Vietnam. It will be too long a quest, Captain. During the first Indochina War, my Jesuit brethren from the Société des Missions Étrangers tried to recast the traditionalist Vietnamese spirit over a span of a hundred years. They collided with rigid partisanship, deeply rooted Confucian ideals, Taoism, Cao Dao, Buddhist piety and Marxist atheism.”

“I conceive no other grand plan to pull this through, Enzo. Too many are dying to maintain the power structures in Saigon and Hanoi as they are. No one sits back and wonders how best to derail from Vietnam’s present tragic story. A pursuit of common ground away from military might.”

“Scusate mia volgarità… But sure as hell won’t be by bringing in the Hanoi gang into Saigon.”

“All this mess stems from a major geopolitical blunder at the close of World War II. Vietnamese nationalism was strong and had direction, but the West considered old Uncle Ho too radical and brushed him aside. France wanted a front seat again in Indochina. The United States sided with the French imperialists. Supported the Vietnamese oligarchs in Saigon who were in collusion and political bondage with French colonialism. A more advanced arrangement could have been negotiated.”

“I am not one of you clairvoyant kids, but I sense you’re going native, Ruddy.”

“Don’t believe I’m for appeasement with the insurrectos. They have done too much damage to South Vietnamese society. But, I’ve fully immersed myself in the Vietnam conundrum.”

“Vietnamese existentialist reality is too difficult for the Western mind,” Santangelo groused. “One side is willing to die for a pantheon of worldly deities, the other for no gods at all. Don’t expect US commanders to invest engagement time trying to figure it out. They want to clear the field and go home with the least loss of assets.”

“I insist there are less bloody options.”

“Bless you for that. But these should have been put in place before we arrived here. Tragically, it’s a dance to the death now. May God forgive us.”

“Still time to go to the root of this conflict. Fix the broken. More civic rights for the peasantry. Instill less veneration of elders and boost the younger generations. Degrade the warlord tradition and blow up civil services. See what I mean? Still, there are too many tensions pushing against a common path. In Vietnam, the past crushes the present. The present becomes the past.”

“For sure, buddy. A weird history. Until just the other day, a child emperor ruled over this country, for Christ’s sake,” Santangelo protested.

“Political manipulations. The imperial powers exerted their cunning on a confiding Vietnamese society. Propping up puppet rulers. Too many historic tragedies in this land,” argued Cardenas.

“I agree, mio signore. Machinations to push back societies to past ages,” Santangelo asserted.

Cardenas nodded. “Now, the National Liberation Front does likewise. Rekindling cultural tensions through nostalgia, tradition, and superstition. Dominance through emotional aggression.”

“I commend your grasp of affairs in this convulsed country. You seem to be proposing a new psychic strategy to counter Viet Cong chicanery?”

“Deterrence by whatever means. Viet Cong ideologues masterfully play on the rural folk’s simplicity with patriotic ideals. Never talk about central political control, state ownership of all commodities.”

“Many South Vietnamese are courageously fighting back. You’ve seen it out on the battlefield,” said Santangelo.

“The Viet Cong mind blotting is highly effective. Many South Vietnamese are secretly looking up to the nationalists. Right under our noses. We may be fighting a losing proposition,” said Cardenas.

“Powerful ruminations, captain. You seem to be implying our boys are dying for a lost cause.”

“I am convinced, but no one listens. We’re slipping on the psychological war. We need to disrupt the hot streams of enemy psychic aggression. How? With stronger sysops weapons and even more intense scare tactics. Stronger counterrevolutionary panic. With whatever means possible before the rebellion becomes massive. All-out war. Before the VC reach full military capability.”

“Hmm.” reacted the chaplain. “There are spiritual or moral issues with sorcery. Black magic trickery offends God’s mercy. Tell me this: Are any of these dark ops tactics scientifically reliable?

Cardenas fell into deep thought. “I must confess its trial and error for now. But it’s not a folly. Early this year, I hesitated about my military career. I then received an opportunity to do sensing experimentation on Nam’s battlefields. You know I am not a spiritualist, but ancient mysticism fascinates me. So, I went for it. Vietnam is a ripe experimental lab because of the animist beliefs and deep-rooted ancestral worship.”

“Does Da Nang command know the insides?”

“Not all details. It’s a top-secret US Army program. Based on research by Virginia Tech parapsychology scientists. It also involves a modern warfare studies unit at Fort Riley. They call it Intelligence Innovation Futures. That’s all I can tell, Enzo. I hope you can help get me some operational leeway from headquarters without spilling the beans.”

“Yours is not a confessional secret, but you can trust my discretion. Nonetheless, I grieve for Vietnam. Despite all the ancestral spirituality, it’s reverting to rapacious nationalism, primitive atrocity, and social depredation of the weakest. I pray to Christ that our presence here will provide a recourse for events.”

Still feeling uneasy, Captain Cardenas shuffled himself about the bunker. He lit up a cigarette. “I did not want to raise the issue. But, for our current counterrevolutionary tactics to be effective, we’ll also have to push politics and religion aside. Make it hard, cold shock propagandizing.”

“Ruddy… Let me confide this with you. Colonel Maguire believes you dedicated too much time to Cold War spy craft. During your post-war assignments in Germany and South Korea.”

“I did learn a deceptive trick or two when dealing with the East German Stassi in Berlin,” confessed Cardenas. “However, that is backstage. My concern in Vietnam is that politicians in Washington sent us to fight this war without an ultimate military goal. I am against using good soldiers to prioritize political objectives.”

“You do know your Clausewitz tenets,” Santangelo quipped. “Yes, there seems to be no exit criteria, duration policy, scope, or a military transition plan.”

“The lack of martial symmetry is because it’s an undeclared war,” said Cardenas.

“Nevertheless,” Santangelo stated, “worse than the immorality of occupying Vietnam as a foreign power would be if we abandon these people to an atheist regime. So many Christians migrated south after partition in 1954.”

“This will be a protracted war, Father Enzo. The adversary wants it that way. Attrition. It gives them time to mess with our psyche and the people’s will, here and back home.’

“We are expending too much blood and ordnance in tit-for-tat attacks against a ragtag guerrilla.”

“Not for long,” predicted Cardenas. “Recent intel tells us that the Central Highlands will soon become major battlegrounds with the NVA. That’s another facet of their psyche warfare; Hanoi must soon project tactical victories to the world.”

“It seems so. I’ve heard that the grunts are lately running more into fully uniformed soldiers and heavier caliber resistance,” said the priest. “I should think a heavier force as an opponent is more in tune with the American style of warfare.”

“Our soldiers are decent warriors. We fight any battle to its final consequences. We try hard to follow the absurd laws of war. To that account, we need to determine how many of the South Vietnamese are willing to fight alongside us to the end. Stand with us until a final victory,” said Cardenas thoughtfully.

Santangelo exhaled impatiently. “The truth is that many good men are dying here. Many innocent civilians are killed for a Communist cause. There is the everyday displacement of villagers. Still, I don’t see a final design for future governance in South Vietnam. The only unswerving goal I see by the government in Saigon is to stay in power.”

“Aha!” grinned Cardenas. “This soul-searching session is becoming mutual. Certainly, our presence here is becoming murky to the eyes of the world unless we devise a solid military-political strategy.”

“At least we are not here for the gold, like your historical friend Cortés or the French before us. That makes us better in God’s eyes,” the chaplain grinned back.

Cardenas rubbed his chin again. “So, Enzo? If I dispute my commanders, am I sinning of hubris or indiscipline? Dereliction?”

Santangelo thought for a while. “Do you have whiskey in your duffel bag?”

The captain stared hard at the Chaplain, trying to decipher the request. Santangelo smiled with mischief.

“Chaplains gotta socialize too, you know. I dare confess this to you, sometimes I feel all worn out. Saipan, Okinawa, Korea, and now Vietnam. I’ve almost depleted my dead soldier prayers and grief speeches. Been at war too long. Only with God’s help, I keep going.”

Cardenas went to his footlocker. He extracted a bottle of Jim Beam. This was his favorite firewater since his early soldiering days at Fort Hood. As a young man, he migrated to Texas from Mexico’s inland Quintana Roo. As a child, he imbibed tepache. A local ferment from pineapple rinds. It was a brew from the days of his Mayan ancestors.

“Didn’t know you were a boozer, Enzo. Except for the sacred vino.”

“Officers frequently invite me to their club for informal disclosures. Most are of a Protestant bent and don’t follow our confessional rituals. I listen to everyone. A fellow chaplain once said that having one drink too many at the Officer’s Bar causes enough despondency in the drinker for penitence. This provides a good moment for a chaplain to deliver a sermon about God’s love and forgiveness.”

Cardenas filled two small plastic cups with whiskey, passed one to the chaplain, toasted, drank, and sneered. He composed himself quickly. “The Lord has gifted you with a holy pair of ears, Enzo. So, without revealing confessional secrets, what irks my fellow officers at the bar?”

The chaplain downed the whiskey in a half-gulp. “They ask if our Christian God authorized them to kill heathen guerrillas.”

“That’s a tough one, Father. Is there a sensible reply?”

“The moral landscape of war is too complex, maybe even for God,” said Santangelo with a sad tone of lament. “War opens up a moral labyrinth for all its actors. Many ethical tightropes and spiritual quandaries.”

“I always quote one of your short sermons at Hill 54 about killing, Hesitation to do so, or remorse. I tell my men that once you press the trigger, you are responsible for the consequences of that bullet. Same when you press the button of a nuclear-guided missile, throw a bomb, or shoot an artillery shell. I tell them to trigger wisely.”

“Rightly so,” sighed Santangelo. “Judiciously, never mercilessly. That is the difference between murder and gallantry in battle.”

“Battle guilt is a bad companion of war. Lasts a lifetime,” said Cardenas.

Santangelo drank the remaining shot in his glass. “An old sarge asked me once if there was any forgiveness for euthanizing a mortally injured guerrilla. I usually explain that moral judgment comes from deep within the conscience, not from the act itself. Since conscience is a gift of God, you must first forgive yourself by seeing it as an act of compassion.”

“It’s a very convoluted moral philosophy, Enzo. I have constant debates with my combat medic, Josiah Rawlings. He considers war an infernal travesty.”

“I’ve also discussed many moral quandaries of soldiering with your medic. He’s quite a character. A street philosopher,” said Santangelo. “Thinks he knows all the answers to our moral dilemma in Vietnam. So, he comes to me not to seek counsel but to advice.”

“Ah, yes,” Cardenas quickly responded. “I have a pending conversation with Rawlings about his soldiering attitudes. He is a contrarian, alright. But so am I, so let’s stick to the matters at hand.”

“As you wish, Ruddy. But Rawlings is a case in point of why faith reinforcement ministry is strongly needed. There is a growing opposition to this war among the ranks.”

“Not much we can do about that,” affirmed Cárdenas. “Not easy to be righteous and forgiving when you´re staring at the business end of an AK-47 muzzle. That is also my dilemma with my commanders in Da Nang.”

“I always give my reassurance and encouragement; offer prayer to those in the field. The peaceniks back home? I’ll let them answer to their conscience. Who knows, they may be right after all. They see malarkey in our war-faring politics when we don’t.”

“I’ll agree to that in a way,” huffed Cardenas. “The politicians who sent us in to fight their wars just as easily walk us out without any remorse. No consequence for their soul because their entire outlook on reality is through the lens of power. That is why I only respond to field commanders, not civilian advisors.”

“Then respond to yours here in Da Nang, and your spiritual turmoil is over,” proposed Santangelo. He pointed at the captain with his whiskey cup and extended it for a refill.

“It’s not that straightforward, Enzo. Tell me this: do you know who sets the ground rules in Vietnam for an ambush at the bush?”

“Field commanders,” said Santangelo. “They run the battle operations.”

“Not so. Our rules of engagement are determined by diplomats, political advisors, and politicians. They sit at bureau desks far away from the lethal ambush site. Ultimate protocols originate from think tanks throughout the United States and the Department of State. It is why I insist on letting them solve the Vietnam quandary. Not thrown unto the shoulders of professional soldiers.”

“True. That’s why I say the hippies may be right,” the chaplain said with a snide. “So, back to theme. What true ballast is weighing down your conscience?”

“During my infantry days at Cu Chi, I was often called to our Embassy in Saigon to be briefed. Scolded for any unconventional response to Viet Cong brutality. Our grunts cut ears and gave VC prisoners the death card. After those embassy briefings, finding out who pushed the rule buttons was easy.”

“We must tread carefully with battlefield rage Ruddy. War crimes do bring moral guilt, plus political karma. The Geneva Convention…”

“No Geneva rules in Nam,” Cardenas retorted. “We soon figured out that our actions needed to occur outside any moral setup. What occurred to Lieutenant Colonel Cavazos —may God care for his soul— over at the Plain of Jars and to my uncle at Cu Chi made me realize field commanders were on our own.”

“Ah yes, the maverick Green Beret Cavazos,” said Santangelo. “He led an A-Team in covert operations at infiltration routes in Laos. Our Special Ops Mortician Lieutenant Santos briefed us during a top-secret meeting on forensics about his capture and merciless execution. I was consulted because the family requested a death mask and cremation of his body.”

Cardenas nodded. “Before his demise, we ran long patrols at Pleiku. He wasn’t shy about crossing into Laos and Cambodia. The Colonel pulled me into sysops work. I still can’t get over how his captors brutally wasted him after he was disarmed and wounded.”

“Such events are out of my moral radar. Ruddy. I only hope that if we follow the political directives of wise men in Washington DC, we’ll conclude this swiftly. Go home, I estimate, by the end of next year. We’ve been here too long already.”

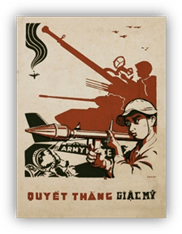

Cardenas stared fancifully at the holy man, trying to detect irony within the statement. “We won’t be going anywhere anytime soon. Myself? I won’t leave Vietnam alive until the capture of the slayer beast Quyet Thang and his political assassination gang.”

“Obsessive revenge is as sinful as arrogance, brother Ruddy. And I hear this culprit is nowhere to be found.”

“The bandido is nearby. Probably spying on us every day. His network deals with necromancy to tap deep into traditional Vietnamese animist beliefs. Every Viet family extends itself from the living to the dead through ancestral worship. The Quyet Thang people are experts at it.”

“Our Savior Jesus Christ did away with ancient pagan practices,” preached Santangelo. “It’s disturbing they still are prevalent in these parts of the world.”

“I have a special team working on Thang’s whereabouts. The latest intel tells us he is operating underground in Da Nang.”

“Tell me a bit more about this troop of mind-reading soldiers you’ve set up. It defies all military logic and religious thinking.”

“My man, Enzo,” jumped up Cardenas. “Gallagher and his staff do keep you up to date.”

I have private dinners with the Colonel at his quarters or with his staff at the mess hall. Our conversations are social, truthful, and confidential. Does this also cause you resentment?”

“No, Padre. It surprises me that you know so much about my classified mission.”

“We are all military men, Ruddy. Commanders exchange relevant information with each other. I exchange moral thoughts with all. Tell me about this psychic team of yours.”

Cardenas served the next round. He savored his brew lightly and set it down while Santangelo drank in full. Cardenas pondered an answer.

“What’s your quest in the spirit world of the Vietnamese?” the chaplain insisted.

“Nothing satanic, Enzo. Everything is very scientific. My troops? These are good men. Quite traditionally religious, with an exception or two. They possess certain God-given gifts, a set of unconventional senses I think we can use to fight this unconventional war.”

“Keep all metaphysical away from this already too bizarre conflict,” Santangelo advised.

“You know that the rules of engagement call for proportional reaction, as pontificated by Sun Tzu. Or was it Von Clausewitz? Well, no such thing in Vietnam. Everything is unorthodox. Eccentric. So is my mission. North Vietnamese tacticians aim to spark a popular uprising in the South by default of aggression. They latch onto everything historical. Part of the plan involves utilizing the Vietnamese mystical and cultural context. It’s working.”

“Saigon is holding up strong,” said Santangelo.

“The collapse of South Vietnam has not occurred because of our extraordinary counterrevolutionary actions. It’s not because we are killing guerrillas by the hundreds in the paddies or the forests. The more we kill, the more they send in. The National Liberation Front is fueled by a sacrificial warrior spirit.”

“Let’s not devalue the job your infantrymen are doing in the field,” said Santangelo with irony.

“My theory is that engaging intensely with the enemy on the battlefield increases our chances of a disgraceful blunder. If that occurs, we lose international favor, even among our allies. That is what North Vietnamese strategists are pushing for. Tempt us into a stumbling action in the field.”

Santangelo grinned. “Good forward thinking, Ruddy. You know, George Orwell once said the fastest way to end a war is to lose it. But tell me, how do you define your new mission here in Da Nang?”

“Psychic counterinsurgency. A term incomprehensible to many of our field commanders.”

“Ah yes, shadow war craft. The guys with the third eye, armed with covert mischief. It is out of my league. But, does this spooky sword work add any more ballast to your soul, Captain?”

“Nothing but resentment for the condescension attitude of some of my immediate superiors. I want you to counsel me whether my new attitude is sinful arrogance.”

“Not at all. You have a right to make a stand. But other sentiments in your soul do worry me. Let me ask you this. Once you capture this villainous rival of war. Do you want him executed?”

Cardenas became pensive and glared back hard at the priest. “Yes.”

“Cicero is credited with saying that an honorable death can glorify an ignoble warrior. It is best you confront this ignoble warrior in battle and allow him to die at arms. Mercifully. Otherwise, your revengeful hubris will create a martyr for his people.”

Cardenas gulped his whiskey shot. He looked the priest again straight in the eyes. “I will surely meditate on that, Enzo. Your words bring me wisdom.”

“Great!” the priest sighed. He stood and looked at his watch. “We’ve had a good talk and shared some good whiskey. Let’s call this a joyful day. It’s 1500. Got to take leave before I lose my helicopter ride.”

Cardenas put a hand on Santangelo’s shoulder. “Gracias, compadre. You always deliver the solace.”

The chaplain began to walk out but suddenly shifted back. “By the way, thanks for providing me with your assistant, Corporal Ulises Duquel. He helps me with Sunday Mass and ecclesiastical supplies. Over at the Military Sea Transport Service, he arranges for the delivery of wine in bulk. He also makes sure raw wafers are included for the Eucharist. The candles, prayer books, rosaries, and scapularies. All are always in short supply.”

“Yeah, sure,” said Cardenas. “He’s a diligent kid.”

The chaplain stared out at the bunker entrance and lowered his voice.

“Now and then, he does a five-finger requisition of a wine bottle, but it’s still unblessed. So, I look the other way.”

Cardenas’s voice fell lower than the chaplain’s. “The wily kid is in an extramarital relationship with a Mortuary Services officer. But I also look the other way, for now.”

“I’ll have to confess them both soon. Well, a strong abrazo Ruddy. Time to catch my bird.”

Ulises Duque fled the bunker before the chaplain exited. He had heard all the conversation and felt disturbed. Not by the maze of geopolitical pondering.

What was all the crap about an extramarital relationship?

♠