An M-16 burst of fire by Buck Seargent Espino from behind a boulder into the village’s main hut stirred Ulises back to the moment’s reality. On the radio, Cardenas again ordered a full-frontal attack into the village center. Once again, Lieutenant Piper hesitated. Again, the skirmish fell into a calm

Ulises despaired. Why did the captain not land the Cayuse on the plateau and join the fight? Why didn’t he bring machine gunners on the chopper to rake the village and send the snipers off? He knew the answers. Cardenas had crafted the assault on Bao Cat so self-styled and secretive that his marauders were left to fend solo.

Memories drifted back to logistical issues at Da Nang headquarters one late spring afternoon when Cardenas intensified tplans for the hang mission. New orders for the operation were cut. Rookie Lieutenant Jeremiah Piper received the task to hand-deliver the document to Cardenas. He had to take it straight to Cardenas’s small sandbag bunker in rural Chu Lai. The rustic command post sat on the hilltop crowning the large fire support base. The mount was reamed all around with thick bands of concertina wire. Dirt roads and paths slashed open by military Roman plows traversed the hill like open gash wounds. During monsoon season, the paths became muddied, slushy thoroughfares for machines, man, and beasts.

The three battery placements of 105mm Howitzers sat at three small plateaus of different levels. One faced west, while two other big guns pointed east to protect the city. Smaller cannons and high-caliber mortar stations rested strategically atop the highest embankments. The plows had scraped bare the foliage around each battle station for quick deployment of munitions and gunners.

Dozens of tents, underground ammo deposits, sandbag bunkers, a lumber mess hall, and lookout posts dotted the hillock. The surviving vegetation served as camouflage for latrines, shower stalls, and night guard bunkers. The nickname Rumba Hill stuck with the elements of Tango Troop in tune with the band sextet. During rehearsals, troopers and Vietnamese field farmers heard the swing of mambo and cha-cha-cha. This amid the rumble and thunder of the big guns. Ever so often, a a sweet bolero or two. The musical practice usually took place in the late afternoons as daylight hours became longer.

The grunts gave the rehearsals a moniker: The Six O’clock Follies. This in reference to the daily Vietnam News Service Station transmitting positive news about the war. During the jam sessions many weary infantrymen gathered around. They exchanged war stories, drank a Tiger beer, and enjoyed song.

Even so, occupants of Hill 54 considered it a miserable place. Deafening and unsavory in all its 54 meters of height. Constant cannon firing outgoing. Frequent rocket and mortar attacks incoming.

Small, ramshackle, improvised hamlets dotted roadside approaches to the firebase like cheap trinkets on a dingy street walker. The locals offered shabby Vietnam souvenirs, imitation military uniforms, or useless housewares. Fake war trophies made from expended artillery shells hung from facades to send back home. Plenty of cold, local Ba Moui Ba beer from portable ice boxes. Cheap Korean whiskey at every stall. Even at the laundry huts. Cowboys –entrepreneurial pimps and slick side hustlers– offered rural girls and yongy siesta for rent by chanting comical slogans in broken English. Truthfully, some of the boom-boom girls were of minor age.

The grunts at the base knew the Cowboys were mostly draft dodgers from the South Vietnamese army. They also knew that some were lookouts for the Viet Cong. However, they provided a delectable service. When not out in long patrols, guard duty, or cleaning guns, several sergeants took the opportunity to visit the seedy bottom hill villages. Many lonely GIs did the same. They stayed there until nightfall. Technically, as in every area in the deep rural highlands, the hamlets were free-fire zones. Bombed or strafed at any minor provocation.

From the lonely, stark, and badly lit sandbag bunker at the Rumba hilltop, Captain Ruddy Cardenas devised his plan. He proposed to neutralize top Vietnamese insurgency networks and its agents provocateurs. Counter die-hard revolutionaries, such as Quyet Thang, in the highly contested operational area of the First Corps up to the Demilitarized Zone. His spook war now comprised a large expanse of provinces. Quảng Trị, Huế, Quảng Nam, Quảng Tín, and Quảng Ngãi. Da Nang would be the launch area..

His bunker quarters also served as a looking glass for Cardenas to stare back past ages. He searched for patterns of bravado and insane fortitude by ancestral warriors. A superb heroism revered so much by the National Front propagandists, and secretly by Cardenas himself. Whenever someone hinted to the captain at how quixotic it all painted, he revitalized the Hernando Cortés legend. It was his apex reference of plausibility among impossible odds. Exemplary resolve and genial use of offhand battlefield machination. He had an oft-repeated statement he stated to Ulises untiredly.

“The Viet Cong propagandists revive the warrior Trung Sisters, I revive the Conquistador scoundrel from Cordoba, Spain. In psychic warfare, both remain strategically useful.”

In his daily log –as Ulises copied– the captain defined his strategy as invisible counterinsurgency.

Cardenas sustained long conversations with Ulises inside the command bunker about military figures of the past. He evoked how his historical avatar achieved a speedy annihilation of the Aztec juggernaut. Glorified the battles of Cempoala, Texcoco, and Tenochtitlan. In his mind, Cortés was a both a maverick conqueror and a scoundrel. Fought from the top down. A strategy Cardenas constantly reiterated to his commanders in Da Nang.

Ulises did not mind the erratic spiels. The discourses spared him from guard duty down at the wire. In those dialogues, the usual pensive Cardenas was talkative. And surprisingly well read about the historical tragedies of the Americas.

“As the Aztecs after the their fall from Tenochtitlan, I assume that once the Vietnamese rebellion is neutralized the insurgents irremediably will take on the role of a defeated people,” proposed Cardenas.

“It may occur in reverse. The proud people of Nam will again suffer the melancholy of being conquered. A fate they do not want repeated. This is why during the present strife the insurgents will sacrifice all to avoid another downfall,” said Duquel.

“With very little chance,” Cardenas argued. “But, true… Like the Aztecs, they will put up a good fight.”

“To prevail in this conflict, the US military will need to bring much death and destruction to the brawl, Sir.” countered Duquel. “Wipe out half of North Vietnam. Destroy all their industrial, political and military centers. Install into a broken country a democracy bathed in blood.”

“You make tough arguments, muchacho. You have good perspective. But, in no way Vietnam should be turned over to the Communists. From what I’ve seen of such regimes, once in power they become a police state by an elite of ideologues.”

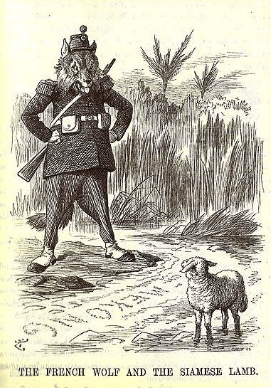

“The conflict between Western allies and the revolutionaries in Hanoi is like a loose tiger and a tied up lamb. Just like this political cartoon I found in L’Humanité newspaper from 1920.”

“As kid at the backwaters of Quinta Roo, I used to walk by my lonely self among cenotes and sinkhole caves. Imagined the battles between brave native Jaguar and Eagle warriors with daggers, spears, and the obsidian clubs.”

“As in Vietnam, the history of Mexico is rife with internal strife and bloodshed. Four centuries after the Aztec debacle, the caudillos and dictators became as ruthless as the conquistadores,” said Duquel.

“True, corporal. Constant belligerent revivals with the old evils. Suppression against the clergy, then the oligarchs and then all types of political inversions during the revolutionary period. Mexico is a surrealist nation. Much as the Viet Cong is doing the same in Vietnam. I feel like I am back home here from a past life.”

“Ah, the captain believes in reincarnation. Fast becoming a Buddhist or a Cao Dai. Chaplain Santangelo wouldn’t approve of that, Sir.”

“I’ve been a soldier since I can remember and seen or practiced every type of violence of man against man. I now believe in any pious idea to deliver humanity from so much turmoil.”

“The monk I befriended at Da Nang professes that in Vietnam during these times –everyone, including us– is under heavy karma.”

“I know about this monk. Keep an eye on him. He moves about in an area of Marble Mountain historically rife with insurrectos.”

“He is a kind soul, captain. Seems holy to me.”

“Follow my order, Duquel. I’ve seen every sort of duplicity you can imagine. Especially in Vietnam’s mercurial war front. And by the way, now that Marble Mountain comes to mind. I need you to drive over to nearby Hoi An early tomorrow. Be here with the Jeep at 0700 for a route map.”

Such conversations made Duquel clearly understand that Cardenas was no conciliator. The captain’s war instincts were like Cortés, of total vanquish. He merely differed from his Da Nang commanders in his approach to the kill. He aimed to demoralize the insurrection from the top and inside out, not one guerrilla fighter at a time. Opting to hit the topmost insurrection chiefs at their secret societies in the towns and district villages. Not harass rustic guerrilla cells inside tunnels, or behind a hamlet.

Cardenas’s aim was to destabilize the warrior spirit. Kill the messenger. Abate the enemy’s stamina by damaging its fighting spirit. Shunned the use of costly assets of mobilizing cavalry troops on Chinooks and Huey choppers after dawn or dusk.

He argued his case before the commanders on and off. His strategy did not require heavy resources. Mere time and willpower. Discern the enemy, then annihilate. A magnificent strategy but only in theory. Duquel’s extempore research duty now needed to help the captain make it functional. He examined annals from the old French archives in search of testimonials of captured nationalist prisoners for tracts of modern Viet Cong operational infrastructure. Spent long hours helping Cardenas string together a coherent profile of contemporary key Viet Cong leadership.

As the data fell into place, the captain carefully materialized a plan to infiltrate ideological cells in Da Nang. With Boi, they recruited trusted local spies. Began to insert eyes and ears into key patriotic societies in Da Nang and Marble Mountain. Additionally, they placed informants in both Hue’s ancient imperial capital and Hoi An’s strategic port town.

Guided by Boi, the Tango Troop music band played gigs in designated venues. Boi always watching out for conspirators. Duquel strongly presumed –gravely feared– that in return, the Viet Cong cadre now kept a close watch on the sextet musicians.

♠