Rocket attack – Marble Mountain

In his careful, frugal calligraphy, Ulises wrote constant log entries. He developed the skill through years of note-taking in college classrooms. Deviating from military tradition, Captain Cardenas gave each platoon a different designation as if it were of company size. He wanted to separate responsibilities. This kept Ulises busy doing diverse entries for each platoon. He usually accompanied the entries with supporting docs or maps. These were carefully encoded with Spanish terms and the differentiated names for each trooper. All in case logs fell into sappers’ hands.

Ulises presumed the triple name was also to brand his unit as a special operations force. Nevertheless, at battalion command, the garrison sergeants referred to the captain’s unconventional company as The Fufu troop. Fucked up fighting unit.

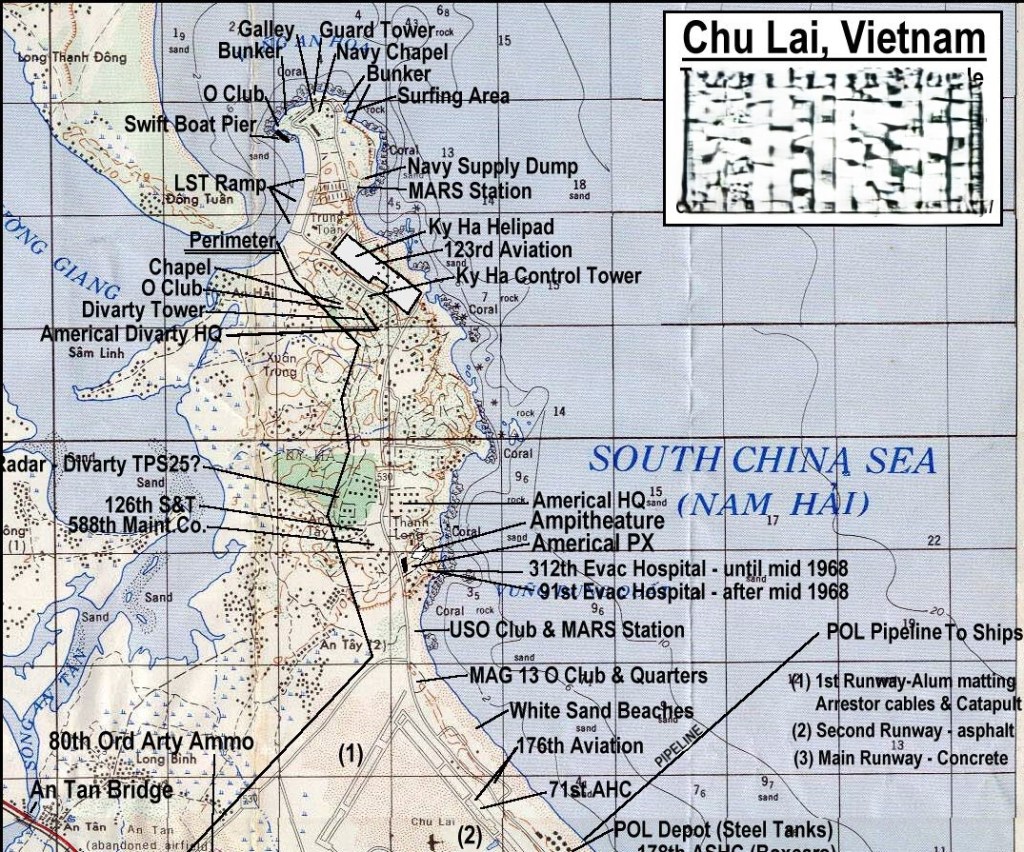

By the end of May 1967, each platoon set up quarters in tents, at sandbag bunkers or rustic tin-roof hooches at Hill 54, in coastal Chu Lai. Thet staked out wherever a safe spot was available. Every soldier had relocated from the Reinforcements Depot barracks at Da Nang. Lead troop Tango settled at the high western end of the forward artillery base. Cardenas quickly designed a small, interconnected camp as a prime operational post for his intelligence project. Far from the big gun batteries for a quieter stay.

Then, the captain swiftly ordered Duquel to set up the musical troupe he deemed necessary for civillian interaction. Ulises scrambled through the company’s personnel records and found six soldiers with musical abilities. He now needed instruments. Instruments were a scarce commodity in the central Vietnam military camps. The Chu Lai airbase served as an air attack support installation since the first US Marine landing two years before. The sprawling compound was named after the nearby Chu Lai River. Chosen by the strategists for its proximity to the coast, ships brought in supplies directly South Korea, Japan, the Phillipines and San Francisco. The base also sat relative to the clandestine Viet Cong camps, and to the infiltrated North Vietnamese encampments by the Laos border.

Ulises made a note about the discomforts of camp life. He jotted down the unusual order he got to make happy music amid the torments of war.

“The terrain and weather make life difficult for the foot soldier. The humid heat, monsoon rains, and thick jungle pose constant challenges to the troop. Muddy roads, flooded tents, and the ever-present threat of attack keep everyone on edge. Narrow trails and old roads crisscross the terrain. A network of rivers and streams, often overgrown, offers limited access to the suspected guerrilla areas. Yet, amid the hardships, camaraderie grows strong among the ever-moving troops. Music and song are always appreciated to break the war front tensions.

The band took shape with diligence from FuFu Company’s top sergeant. The ubiquitous Chuco Tabal scavenged old instruments from supply depots at Da Nang Base, and from the Marble Mountain warehouses. Most belonged to dismantled Marine and Air Force marching bands after their units transferred to less pacified operational zones. With the battered instruments at hand, the sextet rehearsed constantly with Duquel as band director. It soon began to perform in small gigs at local venues around the stone quarry villages near Marble Mountain. The band also played at downtown Da Nang cultural events on Saturdays. The troupe then began visiting selected Vietnamese district schools on weekdays. Cardenas ordered Latin Son to play occasional Sunday afternoon sets at China Beach to justify its existence. These were usually interrupted by rocket attack alerts. The guerrilla were good at keeping the tension switched on and off.

Lieutenant Boi Pham Nguyen kept a list of Central Vietnam cultural societies and of student organizations at the university campus in Hue. He secretly researched locations where Liberation Front recruiters and propagandists operated underground. Cardenas gave precise instructions for the troupe to discreetly identify usual or unusual suspects during the visits. Sniff about for psychic clues that could open a path to Quyet Thang’s whereabouts. Insighting, he sometimes called it. Peering into the enemy’s psyche, unaware that he was being examined metaphysically. Ulises noted the band members felt uncomfortable with the covert mission. Insights did come naturally. Only in the form of a sudden anxiety, a strong itch in the nape. Maybe a rare smell. Everything is undefined and unexplainable. Yet Cardenas insisted the Ulises jot every reaction, sensation, every intuition down for him to study. Usually –he observed– the men suddenly acquired a nervous tension, or sensed a malicious intent when in the presence of certian Vietnamese officials, or village envoiy. Yet, they knew not what it meant.

The band members simply would point it out to Boi, from whom the unease derived. The officer then took notice of a suspect attendee for further, discreet research. Most were minor district officials or university activists. There were always a couple of infiltrated cadres already known to the villagers as Viet Cong recruiters. Their identities were also registered by Boi. South Vietnamese military police later arrested and interrogated them. Always days after the event, to avoid burning the Tango Troop troupe.

It was a strange form of probing the enemy. Opposed by most –if not all– of Cardenas’s superiors at the Tactical Command Center in 1st Corps headquarters. They wanted him in the field wasting away Viet Cong elements, not mesmerizing them like some olive garbed Pan Piper with a Latino tune. The commanders continually devised countermeasures for Cardenas’s ploy. Orders constantly came in for Tango Troop to guard a supply road junction. Protect an ambush perimeter. Ride shotgun with a cargo convoy. Cardenas sneaked in a squad or two from the Whiskey and Papa platoons and kept Tango Troop away from patrol routines.

Ulises diligently took note of the constant put-down campaign by commanders during the Lessons Learned briefings. He recorded every measure devised by Central Command to counter the captain’s warpath approach. Especially when he did not bring to the table useful intel to augment the field commander’s daily combat operations,

Duquel remembered the will of wits that ensued. He described the strategems in the internal logs as continuous and exhausting. Constant distracting battlefronts inside the real battlefronts for the captain. He recalled how in early May, orders came down for Cardenas to float his troop as a wayward unit within the brigade structure. Not attached to any squadron and without a defined mission or logistical battlefield support. Papa, Whiskey, Tango paltoons were to conduct daily search and destroy deployments in villages surrounding only the forward artillery bases, up the highlands towards the Laos border. Cardenas saw it as more logistical blubbery to camouflage the heavy restrictions imposed on his esoteric venture.

Again, the captain complied. He helicoptered lightly-armed squads under Espino’s command into the backwoods where he knew there was to be little contact with the enemy. His intel told him that by now the Viet Cong was slowly moving the insurgency from the rural villages, closer to the urban coastal urban areas. It was there he wanted to meet the foe.

Then, later in May, Central Command hand-delivered to Hill 54 a new Order of Battle. The instructions were filled with a host of military acronyms. Duquel had to decipher them using old military procedural manuals. He used handbooks procured by Tabal from a World War Two sergeant major at the Tam Ky supply depot.

Ulises transposed the document entirely to the logs by typewriter. He simplified the load of acronyms as much as possible. It was a scholarly instinct to aid any future historians interested in Cardenas’s bizarre war effort. Working from his portable desk, Ulises recalled the complex wording, likely intended to convey the solemnity of military hierarchy. The order began with a brief laud for the captain’s recent promotion and his performance as an infantry officer at the Third Corps area. He learned that Cardenas’s new rank occurred at a crucial junction of his military career. After twenty years in service, he could retire early. Go home and spend another twenty years with nostalgic memories of his soldiering days spanning three wars.

Cardenas confided to Duquel that for a moment his mind fogged about where to push his fate. Almost opted to go home to Amarillo, Texas. Buy a small ranch, tend to horses and cattle, and even remarry. He told about how, in a clan ritual his grandfather took him to the old town cemetery as a child. He was shown the tombs of his ancestors. The old man advised him to feel as American as anyone else. Historically, Texas was the land of the Cardenas forefathers.

Yet in Vietnam, such patriarchal reinforcements did not help much to support the captain’s career hesitancy. He sincerely yearned for a rest from warfare and a full recuperation from three combat injuries. It was at an irresolute junction that he received classified intel. Quyet Thang had moved his clandestine operations to a secret location in the Da Nang suburbs.

Cardenas felt a new surge of anticipation. He vowed revenge for Uncle Bernardo’s death at the hands of the Quyet Thang gang back at Cu Chi. He closed his small, special operations office in Saigon’s Information Command Center-Vietnam. He was assigned there on temporary duty while his shrapnel wounds healed. Soon enough, his waning military career took new directions.

As a Viet Cong honcho hunter. He quickly presented his plan to US embassy’s chief covert operatives to capture the Quyet Tahng gang.

On word, a simple handshake and a brief top-secret memo to the Da Nang Battalion bosses, authority was granted for the quest. The captain signed up for another three years. He packed his duffel bag. Hitchhiked a chopper ride from Saigon up to Quang Nam to set up a search force.

The shadow operatives at SOG-V valued his proposal more than anyone. Civilian CIA station officers saw it as a viable counterinsurgency measure in the midst of constant political pressure on the military to stem the Viet Cong insurrection and for the advisers to further stabilize the Saigon government. Since the collapse of the corrupt Diem regime four years earlier, Saigon saw over half a dozen coups d’état.

His proposal was to identify and stake out the new breed of Liberation Front networks in the central coast lands. He argued to his intel superiors that acquiring newly vetted data on insurrection mechanics would be beneficial. Allow field commanders to outmaneuver Viet Cong attackers in a more timely manner. They could achieve this in politicized zones around the Annamite range where militancy was rapidly emerging. Specifically, the strategic Au Shau Valley rimming the Laotian border, with its vibrant network of North Vietnamese infiltration routes.

The north of South Vietnam was fast becoming the epicenter of the insurrection. To set up his plan, Cardenas bypassed chain-of-command protocols. Secretly negotiated with his CIA advisers for a transfer to Da Nang Air Base. Quietly sought permission to set up a small field intel operation at First Corps. Not shy about parrying chain-of-command procedures, he requested special operational assets, including a helicopter for covert flight runs. Also, a company-sized unit of experienced soldiers he was to hand-pick. If necessary, these were to be recruited across different military branches according to special abilities.

During the initial days at Hill 54, Cardenas shared little about his unusual intel-gathering plan. He knew few field commanders would not understand. The focus on Vietnamese civic society rather than battlefield intricacies. The third rifle platoon Tango provided a unit for base defense. It allowed the troop to operate with two platoons outside the base camp when needed. Like a regular company formation. Cardenas considered PWT to be a new type of miniature, self-contained operational structure.

The commanders refused the idea. They would not have each platoon operating as a full-sized fighting force. Cardenas insisted the prime PWT mission was not combat, but intel gathering. His insistence generated new dissent against the wayward field commander. Duquel saw how Cardenas argued that it was all about mobility and light armament intrinsic to the Vietnam conflict. To no avail. The commanders denied the captain the authority to operate as proxy special forces unit. It was not within the traditional Da Nang brigade structure. The discordance was to Duquel’s advantage. It kept him on the move as a courier. He went from Chu Lai to Hue. Moved between Hoi An to Marble Mountain and many times to Da Nang. There, his secret lover’s lair lay in waiting.

Through it all, he saw the captain keep busy with troop selection. He had soldiers with combat experience. He only needed to arm them now with extra-sensory weapons. Over half of the select were grunts who had already served with him in infantry units at Pleiku. He had observed how some manifested certain clairvoyant gifts in the field. In a crude and unsophisticated fashion. The men with keen perceptions did not understand their own faculties. Did not grasp the intricate mysteries of metaphysical insight. Faculties not easily controllable.

No one knew yet how to use them for warfare. Psychic insights were for personal emotions or mystery-driven movie plots. But he wanted to experiment because he believed in its pertinence in Vietnam. A war of psyches. In the propaganda arena. Intensely. It was his job now to hone his soldiers into psychic warfare.

Cardenas correctly supposed that tracking the stealthy Quyet Thang too daunting for an infantry officer with a small troop. The Vietnamese communist ideologue he hunted was a top psychological deceiver. Might have been trained in some ultra-secret Soviet academy specialized in parapsychological sciences. Only his insistence before the commanders on tools different from the traditional military arsenal made it probable. They questioned his credentials for spook warfare. He could only refer them to scientists in charge of developing special spying operations at the War College in Panama,.

In Vietnam, the conventional toolbox included movement sensors in the jungle and body sniffers in the brush. These did not work with the Quyet Thang gang. It moved through the shadow corridors and concealed saloons of the Vietnamese secret animist societies. Their recruitment, indoctrination, and brainwashing protocols required special countermeasures. Invisible methods of detection akin to their clandestine doings. Sensors and electronic sniffers were good for guerrilla movement in the backwoods. The US Army in Vietnam needed metaphysical weapons to unravel Thang’s shrouded indoctrination scenarios. And with his rag-tag troupe of seasoned grunts, exotic musicians, and clumsy psychics, Cardenas was up to the task.

In seeing such a mystifying scenario ahead, Ulises Duquel realized that nothing in his basic military training. Nothing in his formal academic skills disciplined him for the subtleties of psychic warfare. His newly acquired Vietnamese scholarship only slightly fortified his understanding of Cardenas’s type of warriorship. But fascinated by it all, he was willing to do his best.

Upon realizing what his fortunes would convey at Hill 54, Ulises decided not to feel diminished, incapable. After all, everyone in Tango Troop was a neophyte in the obscure sciences of psychic insights and shadow militancy. Only Cardenas seemed to have the basic notions. Uiises knew it was not the correct moment. but already he earned to discover where or how the captain had acquired the tenets of ghostly combativeness. Was Cardenas merely theorizing? Was the captain himself loaded with secret extrasensory faculties and secretly knew how to apply them for a manhunt? If so, the officer kept it most silent.

Since at least in appearance everyone seemed to be on equal footing, Ulises quietly decided to throw himself into the fray with intensity. So far so good. He had acquired an exotic lady lover, the cherished friendship of a Buddhist monk. Plunged himself into the backstory of Vietnam’s tragic colonial history. Most formidable of all, acquired rare, new knowledge about the mysteries of the human psyche.

No university offered a better learning experience in such a short expanse. One handicap only. He now sat front stage in the lethal theater of war. He only had to figure out how to make it survivable. Dodge a sniper bullet from nowhere. Avoid being morphed into one of Lieutenant Kikei Santos’s mortuary statistics.

While typing up the captain’s constant hand-scribbled logs, Ulises Duquel paid close attention to the data fields that fell on his hands. His attentive mind grasped many insights into Cardenas’ intricate views of the Southeast Asian conflict. The Viet nationalists, up in arms, were not battlefield enemies but peer adversaries. He saw them as historical actors of their time. They needed to be understood and defined for posterity. Even emulated in their cunning. Ulises presumed no other infantry officer dared expound such notions about an enemy they were assigned to kill in the combat zone.

Up at Bao Cat, Ulises breathed heavily. He hung stubbornly to life as the cliff heights flooded him with memories of his time as a novice soldier at war. He remembered one particular night inside the officer’s bunker at Hill 54. Both were poring over old French newspaper stories about clandestine Viet Minh networks in Saigon of ten years before. The captain then stood up, stared into the night, and proclaimed a conviction.

“The military conflict in Vietnam is on a small scale. The larger war is staged in the collective psyche of this country. That is where we are already losing this war. It is there we need to fight stronger.”

Much later after that night at the bunker, he remembered another conversation with Jampa Kochi inside a Marble Mountain cave temple. The monk made a similar proclamation, only with different words.

“Vietnam is a country with heavy karma on its national soul. It requires cleansing. Only those who understand it will prevail.”

Duquel was shaken. Two keen minds of different intellect and existential reality had equal intuitions. One trained for war and the other for peace. Even so, they both understood the deep nature of Vietnam’s national tragedy.

So it was. He lay now badly wounded in Bao Cat and many insights and expressions were falling into place. Like the monk, and the warriot Cardenas, he now understood that geopolitical intrigue, more than historical perspective brought together an entire generation of souls and bodies –including Ulises Duquel himself– into the intricate fray of Vietnam . Souls and bodies entangled in a bloody dance of death that Duquel intuited would soon be but a tiny footnote in the annals of warfare. And there, by the bamboo gate of the forlorn hamlet, bleeding to death, he felt angst and loathing.

“Whoever the fuck designed this pointless drama of death and transfiguration,” he mumbled, “should be laid on the guillotine.”

♠