In the Vietnamese back country Ulises Duquel detected an afterlife culture akin to the Egyptian cult of the dead and the Mayan rebirth beliefs. Spiritist acceptance and ancestor worship as the societal norms. Veneration for the departed ruled daily sentiment and emotion in the village and influenced every major decision of Vietnamese life.

He saw small ancestral altars in every village home, incense burners on street junctions, and often, small monuments to the deceased alongside old mountain trails. The deceased shared the same useful spaces as the living. Offerings of food, spiritual money, or trinkets adorned tombstones and temple altars. Invocation and incantation to ancestors everywhere as if the real world were a mausoleum, or the inverse, the spirit world a daily reality. Remembrance and devotion were the dominant ideology in rural Vietnamese life. Tradition was a necessary evil for daily survival.

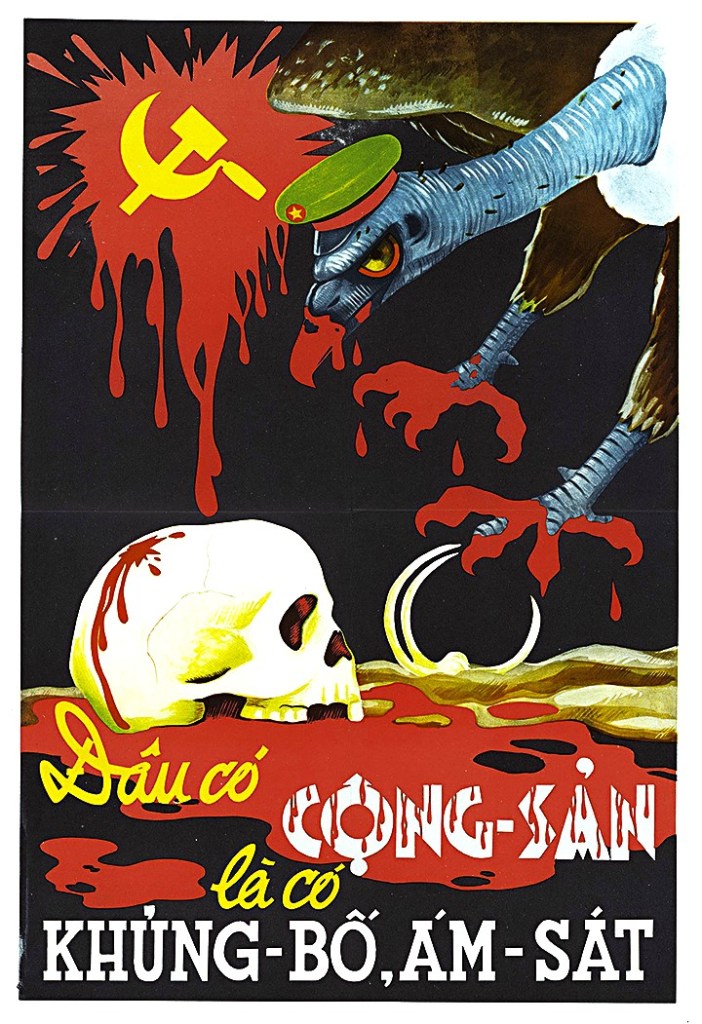

Captain Ruddy Cadenas realized how adeptly the top Viet Cong ideologists weaponized Vietnamese tradition. How in Vietnam history, foreign powers were out to scavenge the country’s meager resources and to eradicate its mystic legacy. He understood that the nationalists, the Viet Minh, now the Viet Cong, patriotically defended traditional beliefs. They fought for soul migration, ancestral veneration, and reverence for the tree, the forest, and the rice seedlings. His only problem was that they did so perfidiously. Dis so under the guise of Communist ideology, which considered such concepts superstition.

Cardenas saw how a National Liberation Front shadow government ruled every town and district in the big cities and border provinces. Under such silhouette regimes, the political cadre incessantly played on the deeply rooted spiritual beliefs of the populace while, paradoxically pushing for materialism and objective reality.

Deftly trained in the pragmatic Marxist ideology and irreligious dialectics, these cadres excelled in their mind-bending spiels. They harped on the spirituality of Vietnam’s past. Its glorious heroes and the sacrificial love for the Fatherland. As an interrogation officer at Pleiku, the captain dealt with captured political cadres disguised as astrologers, magicians, healers, and diviners in the villages. Many were genuine tu tai –traditionalist scholars and historians– from the old French lycée and universities in Saigon, Hue, and Da Nang.

Cardenas resigned to the fact that among the high US military echelon, most of his superiors were indifferent to the cultural and traditional perceptions of the Vietnamese mind. Thus, in a shadowy manner, he devised a strategy to deal with the bizarre reality of a Vietnamese animist landscape. Attempt to fight it out his own way in the fields of psychic warfare. And it had to be on equal terms with his Viet Cong patriotic counterparts.

Yet, Ulises Duquel saw how the captain’s counterinsurgency ploys also had difficult contours. He marveled at how this iconoclast officer creatively understood the strategic value of countering his adversary’s political indoctrination artifices. But Cardenas only retained a small retinue of supporters. A few dark operators at the US Special Studies and Observation Group in Saigon grasped the scope of the task. They managed to grasp the intricate logistics of combat against the Vietnamese occult world as a long-term, strategic gain.

His Tango Troop quickly learned a vital lesson further down the echelon ladder. Placing moles in Viet Cong recruitment and propaganda cells in Da Nang needed more cunning. The captain’s shadow arsenal did not provide enough. Additionally, it needed a more decisive ruse. Extrasensory perception tactics alone were not enough. Luckily, Cardenas leaned on his Vietnamese aide, First Lieutenant Boi Pham Nguyen. His wits, political meddling talents, and loyalty to the captain’s tactical schemes resulted in insurmountable effects.

Boi’s ancestral elitism and youthful idealism ruled his social values. He refused the dogmatism and regimentation of collective thinking. Like Cardenas, Boi would not stomach the dialectics of Marxism and its materialistic objectivity. He preferred individual advancement and personal enterprise. Au lieu Americain, he liked to pun.

In his youth at the Lycée Jean Jacques Rousseau, a top colonial school in Saigon in the 1950s, Boi meddled with nationalist friends. These classmates participated in underground proletarian struggles against French rule. They also opposed the authoritarianism of the Diem regime. As a descendant of the old Vietnamese upper class and its ancestral scholar gentry, Boi quickly mended his dalliances. He preferred the inherited belief of family over ideology. His father had been a middle-echelon French official, a strict observer of the Vietnamese paterfamilias tradition. As the only son growing up with three sisters, he was pressured to join the military service.

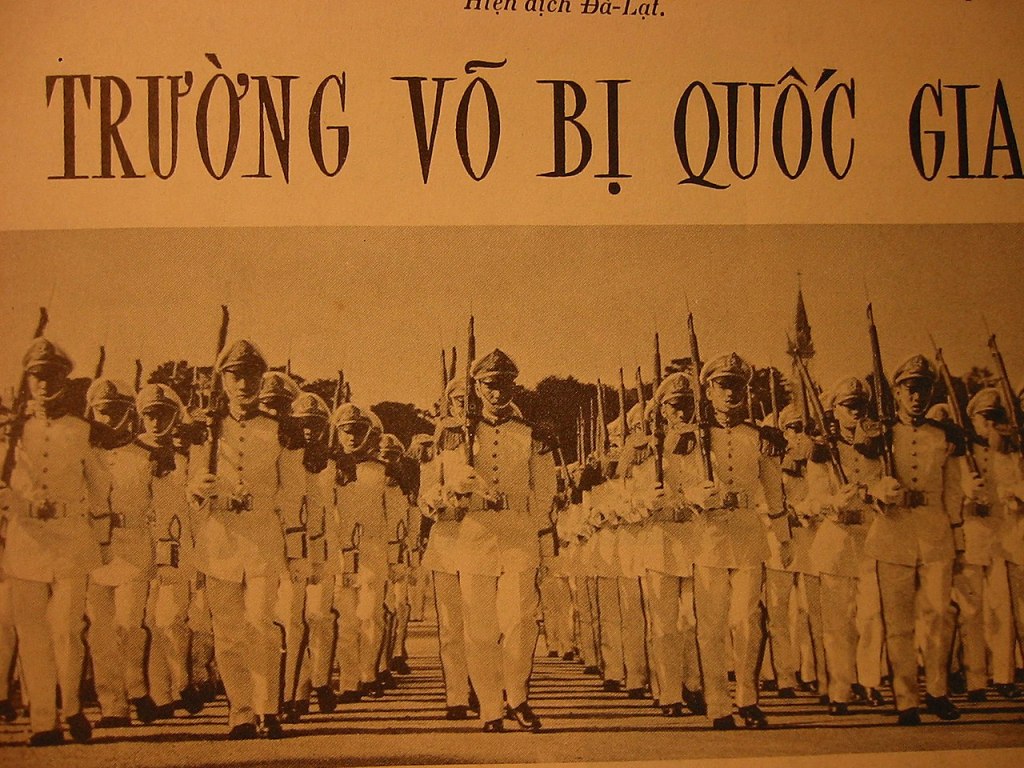

At 18, he chose a different path. Instead of going to the revolution, he went on to became an officer candidate at the South Vietnamese elite Military Academy, at Dalat. It was the years when the US military logistical infrastructure began kicking into gear in Vietnam. Boi was fluent in French and English. In 1963, US advisors sent him to study at the American School of Military Intelligence Interpretation at Fort Huachuca, Arizona. There, he also taught Vietnamese culture to Vietnam-bound intel personnel.

Nonetheless, Boi’s nationalities colleagues gave him access to many political underground’s social codes, security rituals, and ideological nomenclature. Once commissioned, the now elite South Vietnamese officer covertly threaded deep into some of Saigon and Da Nang’s progressive cultural groups. He also covertly entered Hue’s progressive circles where rebel cells existed. This allowed him to set up his own small counterintelligence source network.

Under the tutelage of Cardenas, the captain assigned Boi to guide Duquel in researching historic Vietnamese resistance movements. Both quickly discovered that a young Quyet Thang led a political cadre cell in Saigon. This occurred during the initial Viet Minh insurrection against the French. These cells took on an early vindictive culture against the Ngô Đình Diệm autocracy. They used torture, assassination of government collaborators, and French colonial officials.

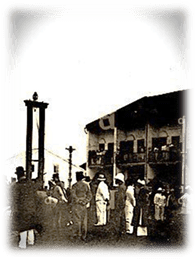

Duquel assumed the rebel blood thirst came from the cruelty of French imprisonment and torture. The obscene public guillotine executions of partisans at many plaza squares across Le Colonial Indochine.

While studying along with Boi Vietnamese lore and the tragic history of Indochina, Duquel tried to understand Cardenas’s complex journey. He laterally –noiselessly– explored the obsessive path towards the quest to quash Quyet Tang and his adherents. After proving his worth as an infantry lieutenant at the Iron Triangle, Cardenas quickly rose in the ranks to captain. He had been wounded twice, by shrapnel and once by a razing sniper bullet to his nape.

In 1966, after two tours of duty, the new captain chose a different path. Instead of retiring and returning to a restful civilian lifestyle, he requested a shift to field intelligence. US Army sysops operations were rapidly developing in Vietnam. This was in response to the growing subversion in the cities by the new Viet Cong leadership. Their intense proselytizing and intimidation campaigns in the villages also prompted a fierce counteroffensive against the insurgency.

US clandestine operations against Victor Charlie initially lacked funds. They also needed experienced leadership. A new type of military asymmetry and little knowledge about the enemy’s face and lore meant trial-and-error tactics. Cardenas felt more qualified than many of the newly minted covert agents sent in from Washington, Korea, and Hawaii.

Soon enough, he was deeply involved in counterintelligence and counterguerrilla operations. Civilian CIA operatives conducted schemes within Saigon’s shadowy world. A world populated by National Liberation Front spies, double agents, and saboteurs. However, Vietnamese lore, tradition, and rebel propaganda methods got the best of his attention.

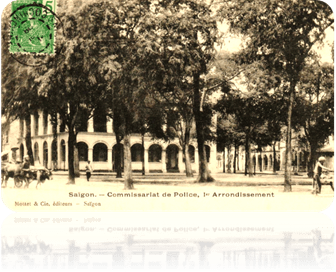

Old Sûreté prison

He was attached to the Military Action Center-Vietnam, where he also connected with top South Vietnamese intelligence officials. During such interactions, he ran into First Lieutenant Boi Pham Nguyen as an interpreter. Boi excelled in vintage Vietnamese vocabulary and was fully functional in English and French. An extraordinary asset for the mission Cardenas was quietly assembling. The studious Vietnamese officer pointed Cardenas to the old Sûreté Archives in Saigon. There, Cardenas later involved Ulises Duquel in a prolonged search for clues to the already legendary Thang. He searched deep within criminal records. Examined intelligence reports and dossiers on the shadowy rebel. Also, investigated the methods of his roaming gang of propagandists, provocateurs, kidnappers, and political assassins. Duquel applied some French language skills from his scholarly delving at Syracuse.

With every new piece of information, Cardenas became ever hungrier for more insights. He sought inklings about a new generation of South Vietnamese rebel leaders to which Thang belonged. This was after the collapse of the old Viet Minh, which resulted from bloody Ngô Đình Diệm repressions.

Intel on Thang was scant. He created a legend of ubiquity. An ability to simultaneously be anywhere and nowhere. Dog-headedly, Cardenas followed Thang’s insurrectional trail year by year. He traced it from his youthful days during the Viet Minh rebellion to his rise as a top rebel commander in the new Liberation Front. It was a movement lethally despised by South Vietnamese politicians and military officers alike. They branded it Viet Cong. Goddammed Vietnamese Communists, as phrased by Boi.

Cardenas patiently did the hard, shadowy trudge. He mostly followed criminal paper trails hidden in dank, abandoned former colonial police station repositories. He also investigated files at the newer, too dispersed, still unorganized South Vietnamese state security offices. US intel was also heuristic in those early days of intervention. American information strategists suffered a steep learning curve in the early 1960s due to many regime shifts in Saigon. Everywhere too little knowledge about insurrection infrastructure. There was less understanding about enemy defensive tactics and clandestine infiltration methods. In those early days, Cardenas discovered that spook intel was a cut-and-try ordeal with many missteps.

He possessed field knowledge and understood Vietnamese animist culture well. This knowledge helped the station chiefs at the Special Operations Group offices set up tricks for psychological warfare. Imagination, the need for fast, effective counterinsurgency measures, and freedom of action moved the team to design the Ghost Tapes. Terror by sound. Crying ghosts, banging gongs, children screaming in fear of apparitions. A brute scare tactic using superstition as a weapon for intimidation.

Shadow operations helicopters and boats with painted-on skulls and Vietnamese death symbols, roamed the skies and rivers. These terrorizing machines embarked on long nightly sorties into villages, rivers, and jungles. Bullhorns blared out the sounds and voices of specters. Tormented souls and ancient warrior spirits begged rebels to lay down their arms. Seek instead a restful peace in their afterlife by denying acceptance of Communist ideals.

With Cardenas’s input about superstition, a nasty team of shadow operatives ingeniously inserted the faux ghoul voices into magnetic tapes. Voices of ancient Vietnamese evil spirits that peasants feared drove people to suicide or a life of opium addiction and dull emptiness. It worked for a while. Desertions occurred, or frightened rebels surrendered and threw down their weapons. Soon, the astute Cong cadres took hold and exposed the airwaves’ voices as silly noises from tape players.

The ruse taught Cardenas how ancestral fear becomes a weapon of war. But, as the slick Viet Cong became slicker, a new repertoire of psychological warfare schemes was needed. A tactic he called misportrayal.

The captain plunged deeper into the old French dossiers. He aimed to pinpoint weaknesses in the rebel ideological dialectic. He focused on the ties between political units and identified flaws in Liberation Front recruiting synergies. Sought a ploy to counter the increasingly aggressive nationalist push into Saigon’s always stumbling South Vietnamese political fabric. His focal point, however, was always Quyet Thang.

When transferred to Da Nang, the captain brought with him the new type of war effort mentality. Became impatient with his field commanders. Their insistence on baiting the Viet Cong into a classic firefight frustrated him. He saw such outcomes in the battlefields of Pleiku. Guerrilla fighters were wasted, but the rebel ideology survived.

He had been there and done so. He saw that for every dead Victor Charlie element, five more emerged from the shadows. They sprung from the mortified rural villages, the mistreated family clan, the politicized university campus. The Lycée radical circles. Institutes in which French colonial arrogance and collaborationist elitism still danced in the halls and classrooms.

Grievous, patriotic secret societies. Animist sects allied with the spirit of ancestral Vietnamese warrior mysticism. They nourished political and cultural resentments in youthful and old minds alike. Fueling the local Vietnamese rebellion on a national scale. It was at that juncture, in that precise ideological battleground, where Cardenas wanted to put up a counterinsurgency fight.

If only his new slew of field commanders at Da Nang base allowed for it.

♠