Since the start of 1967, most brigade commanders in Da Nang felt overwhelmed by so many reports about lessons learned. They believed the playbooks only thickened any rapid annihilation strategy like cutting through lard on an overfed hog.

As Ulises felt his life ebbing away at Bao Cat, his mind went back to a string of ego tussles at base headquarters. By becoming an unwilling witness, he slowly began to learn of the captain’s unusual battle scheme. The battalion commanders argued hard over viable operational procedures to wipe out Viet Cong guerrillas at a fast pace. All the while adhering to the traditional order of battle. But, each had a different design for diffusing insurrection in their area of operation. To their Westernized military minds, each guerrilla cell likewise had a single-minded mission. Simple and lethal. It sat at the end of their Kalashnikov assault rifle’s muzzle. No need to be creative, no logistical complexities. The best tactical antidote to such straightforwardness; the best counteroffensive must always be a search-and-destroy mission.

Captain Ruddy Cardenas saw it differently. The National Liberation Front’s modus was predictable if deciphered properly. True, the adversary’s tactics varied, but towards the same end. After a year in search-and-destroy in the Iron Triangle, he had seen all the options. Strategies changed according to the logistics available and depended on the political climate of the operational zone. Open battles would occur in one geography, clandestine actions in another. The objective remained unchanged. Confound the adversary

Hanoi’s and the Viet Cong’s general battle order could be anticipated. This was possible only once the historical mainsprings of Vietnamese resistance movements were well understood. Very few commanders had or took the time to do so. They focused on daily performance on the battlefield. No time or interest in sitting back to absorb the deeper complexities of Vietnamese insurrection.

Ancestral rebellion influenced the style of rebellion among the rural peasantry of the South. French repression history also played a role in the North Vietnamese Politburo’s war mindset. Additionally, understanding South Vietnamese material aspirations was key in designing an effective defensive strategy against the rebel onslaught. These elements need to be expertly shuffled into a coherent outline. Political opportunism on all sides also needed to be factored in.

Cardenas’s commanders at Da Nang told him there was no time for that. Let the historians figure it out later. Combat operations, not geopolitical theorems, needed to be prioritized. The captain exasperated. The commanders lost patience

Bad blood ensued. Cardenas persisted in looking back into the insurrection timeline, not so much into the treeline. He tasked Duquel and his interpreter Boi Pham Nguyen with unraveling for him the workings of the Asian warrior mind.

While waiting for a final bullet at Bao Cat, Ulises recalled their research from the past five months. It focused on Vietnamese military history, and it shed more puzzlement than clarification. Millennia of acculturation in Vietnam’s history. Centuries of Chinese Confucian morality. Reverence for duty. Ancestral piety. Rigid filial hierarchies. Indefinite and heroic sacrifice for the Fatherland. Worship of the elders and the venerable. A passion for heroes, a ferocity borne of despair and haunted valor. Precepts and concepts foreign to a Westerner’s strategic mind.

In such military matters, Sun Tzu flows directly to the vein. Cardenas knew how psyched-up patriotism shaped and honed the Vietnamese nationalist spirit. A culture of courage and righteousness to the death. A cultivated will to die or kill for the homeland. And with a vast degree of stoicism, a sense of duty, and a fiercely sacrificial warrior spirit. Often driven to extreme cruelty against an enemy.

At Bao Cat, it all made sense to Duquel. A ruthlessness, like the delayed final bullet. Why was the sniper dallying? Was it to increase his suffering? Did a slow kill have more tactical value than a fast elimination of a battlefield rival?

The compressed Vietnamese combatant psyche perplexed US commanders equally. They continually differed and collided over battlefield procedure as resistance flash points multiplied in the Central Highlands. The flare-up of a guerrilla cell one day. Tomorrow, a North Vietnamese battalion. Then both merged, or other designs and patterns of attack in between.

Headquarters never ceased trying to straitjacket Cardenas into submission. At Da Nang operations centers, infantry battalion chiefs demanded adherence to conventional battlefield protocols. One main objective prevailed. Neutralize the heavily infiltrated First Corps area at the top of South Vietnam bordering on Laos. Instead, the captain contrived abstract intel operations parallel to the daily combat action. The colonels running the rules of engagement at Field Corps One demanded an enemy body count. Cardenas parried their directive and opted for minds and hearts of the local populace.

He insisted on a counter-subversion agenda. Prying deep into urban Vietnamese cultural societies. The captain believed this was where the roots of the nationalist fervor lay. The strong will of the Vietnamese resistance. Neutralizing the partisan fervor would neutralize military belligerence.

Ulises didn’t know it at first, but Lieutenant Santos discreetly collaborated with Cardenas. It was all about ideological forensics. He secretly instructed the covert operations mortician to teach Ulises some investigative tricks of the trade. Skills to help Ulises identify key material evidence during his field research. How to recognize signs of ideological identity in corpses, or in the scant dossiers on Quyet Thang. She complied, not out of a passion for spook forensics but simply to follow orders. Ulises later found out Kikei disliked the captain’s shifty, prowling ways.

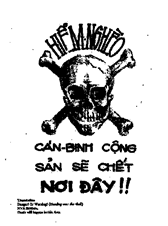

Meanwhile, battalion commanders sent more and more grunts into the bush to hunt down guerrillas. Inversely, Cardenas sent his Tango Troop snoopers to the raided villages as hounds. Their mission was to gather propaganda fliers, pamphlets, training artifacts, or telltale personal or material items. Collect fingerprints. Gather love or filial letters left behind by fleeing or killed guerrillas. He hoped these would paint operational and political maps of insurrection and rebellion mindsets.

Define a fighting spirit. Outline a trail to a key rebel cell and its extended political network. The cadre and pamphleteers. Boi and Duquel took photographs. They classified any identifier weapons and papers. Carefully examined and cataloged personal artifacts left on guerrilla corpses or in hideouts. Orders were to scour wide and deep into any captured Viet Cong lair.

Cardenas argued that such minutiae intel offered more strategic gain. In contrast to counting and photographing dead VC bodies for the international media. It was as a practice the sysops experts in Saigon dubbed Grey Propaganda and he avoided it. Such a gross exhibition of enemy cadavers offended the captain’s moral code and piety.

His field commanders thought otherwise. Insisted on rapidly staving off any buildup of foe troops in the highlands. The order of battle was to destroy enemy concentrations larger than battalion size. To them, fractioning the insurgents into small guerrilla units meant faster annihilation. No need to improvise outlandish offensive schemes. A good rifle company would keep matters at bay. Three gunships provided support for the mission. A couple of napalm-dropping Phantom jets added firepower. Enemy positions were continuously softened by intense artillery from the forward-facing firebases.

By mid-1967, everyone was aware of adversary activity in the Annamite Cordillera. National Liberation Front guerrillas and North Vietnam People’s Army regulars were digging in throughout the region. Every American element operating in the area knew it, from top generals to lowly private first-class grunts. The guerrilla’s domains were the forest underwoods of the A Shau Valley.

And it worried Americal Division’s battalion commander Harry Maguire. He knew that under his nose, the Victor Charlie were setting up insurrectional enclaves. Combat units that led to every coastal city in northern and central Vietnam. American strategists chagrined about how paramilitary bastions kept springing up on the outskirts of already pacified villages. They continually appeared in provincial districts as if a large-scale offensive trap were in the making. Warriors and weapons infiltrated from the north through the Laos border. They arrived on sampans through Da Nang Bay disguised as seafaring merchants. Some posed as itinerant farmers in the rice paddies. Others were radicalized university students. Maguire, the seasoned World War II veteran –a senior infantry officer’s officer in Korea– kept an eagle eye on it all. Irked by the unconventional stratagems of the Vietnamese war theater. Yet, focusing on his best offensive standards. In parallel, the Viet Cong cadre’s relentless 360-degree propaganda militancy enticed Cardenas into equivalent action.

He strained for insights into the insurgent’s motivations, its hierarchy, and operational design. He sought deeper awareness of the Vietnamese warrior spirit. In his own Sun-Tzu manner, he inferred that with adequate intel, a small Special Forces team could decapitate a rebellion at each local level. A Ranger commando might suffice at wider ranges. At most, a company-sized Air Cavalry force would accomplish the task with battlefield precision from top to bottom. Not in an inverse manner.

During the strategy meetings at Da Nang command center, Duquel recalled how the captain parlayed his cause. The chiefs listened until they heard him no more. He soon sensed the captain’s mounting frustrations and disappointments. Cardenas sat in his sandbag bunker at Hill 54 late into the night. He poured over old maps and weathered documents extracted from dank VC tunnels. He reviewed every French Colonial battlefield ephemera he could find. Try to decipher the bigger insurrection game plan with every battlefield clue.Ulises saw it as n ot an easy task. By understanding the wellsprings of the Communist revolution in Vietnam, he could catch the conflict’s direction, depth, and resistance capability. Anticipate every move of top rebellion enforcers such as Quyet Thang as the focal points of the insurrection.

Yet insistently, his military bosses disliked and rejected the captain’s research-centered gambol. They were upset because they recruited this very capable infantry officer to charge and fight. Kill off the Viet Cong injuns by following the traditional US Cavalry mindset. Now, the chosen warhorse had shapeshifted into a pensive, prairie scholar. They especially disliked the captain’s psychological warfare vocabulary. Abstract conflict. Psychic disruptions. Acceleration of vulnerability. It sounded to them like loony bin gibberish.

Sappers and Viet Cong ambushers were lightly armed yet heavily motivated. They wasted away good infantrymen in jungle nooks, rice paddies, and camp perimeters. Meanwhile, sysops operators tied up needed soldiers for their spook counterrevolution efforts. The brass in charge of daily field operations had their doubts. They thought that spreading loathing and fear among superstitious villagers was a waste. Not a good use of battle time and fighting resources.

Maguire wanted battle rattle. He was not for ghoul noises pouring out through helicopter foghorns or bombardments with surrender leaflets. In his operational area, it was a search-and-destroy business. The Vietnam mission required pragmatic attrition, counter-ambush tactics, and well-placed Claymores at ambush escape routes.

He left the politically sensitive raids into Laos and Cambodia to the CIA’s invisible operatives. They knew how to operate in the shadows, kill, and destroy, leaving no tracks. The task for American field officers at First Corps was to secure the strategic villages. They had to pacify those still in arms. Hand them over to South Vietnamese political district chiefs and military officials. No geopolitical encumbrances. No scholarly ruminations were needed at headquarters level.

But Cardenas knew otherwise. Many allied Vietnamese administrators were not of top caliber. Some were not even trustworthy, possibly double agents or simply negligent. A long tradition of vassalage and centuries of resisting French colonial autocracy tempted some towards social elitism and corruption. There were still too many ambitious warlords serving the colonial powers. The more brave and upright suffered intimidation, kidnapping, torture, or assassination by the likes of Quyet Thang’s ideological teams. Such political saboteurs needed to be urgently neutralized

Maquire left the politically sensitive raids into Laos and Cambodia to the CIA’s invisible operatives. They knew how to operate in the shadows, kill, and destroy, leaving no tracks. American field officers at First Corps had a clear task. They needed to secure strategic villages. Pacify those still in arms and hand them over to South Vietnamese political district chiefs or military officials. No geopolitical encumbrances. No scholarly ruminations were needed at his headquarters.

Cardenas cranked up. Large flanking maneuvers needed approval from three brigadier generals on the American side. They also required approval from five on the South Vietnamese side and ten local village chieftains. Better to continually send in small, well-trained, tried-and-true sysops units. Focus on counter-tactics. Disrupt and demoralize the slippery and wily rebel cadres and their lackeys.

Drop more leaflets, less napalm. Coupled with civic action by taxing the landlords more and the artisan rice producers less. Good public health and schooling. Fair distribution of farming land titles. Stronger protection among the peasantry against Viet Cong tax collectors and government bribery. Focus civil action on hardcore partisan rebellious zones. US commanders had the maps and knew where they lay.

Cardenas had already proven his worth in field operations at the Iron Triangle. Now, he wanted to prove himself as a psychological warfare strategist. The day’s first order: Capture the quintessential Viet Cong bigwig, Quyet Thang.

Observing it all from a side view, Ulises Duquel also sensed how Cardenas felt misread by his bosses. At times, he seemed to them like a drunken high-wire acrobat, teetering on insubordination. Trying hard and dangerously to match the psychological wits, psychic oddness, and crafty ruthlessness of the Viet Cong political honchos. The captain took on a too-difficult task. Ulises soon understood that to decipher the inner workings of the insurgent warrior mind took long-winded, very scholarly research. Not mere, raw field intelligence gathering.

In Cardenas’s military thinking, the US had entered a civil war driven by ancestral strife and unresolved colonialism. A conflict fueled by imperialist greed for resources. Cultural disdain from the outside world played a role in many of the misunderstandings. Impatience by the Western powers with Vietnam’s so-called backward traditions. Cardenas preferred that the South Vietnamese engage in direct conflict with their Hanoi rivals without a third force added to the drama. The United States military –he preached to all who listened– should limit itself to a neutralizer role against Communist ideological encroachment. Though a man of arms, he believed Vietnam’s crucible required more civilian arbitration by diplomacy, less war of attrition.

This stance piqued Duquel’s curiosity. How to achieve? he asked Cardenas constantly. Cardenas always had a quick reply. The West needed to outsmart the designs of international communism at a bigger scale. Not use Vietnam as the dissecting laboratory.

As the captain’s amanuensis, Duquel knew the officer’s anti-communism to be visceral. Cardenas despised centralized political systems. His experiences in Korea as a volunteer soldier contributed to this view. His studies at the War College in Panama on Stalinism, shaped his beliefs. Additionally, his work as an intel officer in West Berlin shaped his understanding of the objective reality mind. Realized how the struggle for the proletariat became deceptive to the masses. With a lower dose of venom, he was also critical of French and Japanese colonial usurpation in Vietnam during the 20th century

Duquel observed it all through his academic discipline and intellectual discretion. He was fascinated by how a complex political and military conflict like Vietnam’s could produce such contrasting iconoclast warrior spirits. One was Captain Rudolfo Cardenas, who stood firmly on the ideological right. Another was his archenemy Quyet Thang, who sniped at neoliberalism from the far left.

Then, the feuding polemics among US commanders on how best to crush the insurrection. In a sense, Duquel felt privileged to witness the leadership frays in all their rationality. And to behold the fierce patriotism of a rustic peasant army defying the might of the American fighting machine. A unique warrior psyche will breed a unique war.

Overall, a master class in 20th-century military history. It would be worth a scholarly treatise in his mature academic years. If he could only survive the experience.

♠